Butch Cassidy’s “Lost Manuscript” a Hoax

posted on September 2nd, 2011 in Andes Mountains, Argentina, Bolivia, Butch Cassidy & The Sundance Kid, Recent Discoveries

Anatomy of a Farce

By Dan Buck

Earlier this summer, the Salt Lake City Deseret News published an article, “Lost Butch Cassidy Manuscript Found,” by reporter Michael De Groote, disclosing the discovery of a “long-lost manuscript” said to be the autobiography of the Western outlaw. Brent Ashworth, a veteran Provo rare book and document dealer, had recently purchased the manuscript, “The Bandit Invincible,” on Abebooks.com. He told me this week he had paid about $12,000…

Ashworth showed the manuscript to Larry Pointer, author of the book, In Search of Butch Cassidy, which argued that Spokane business man William T. Phillips, the writer of another version of the manuscript, was in fact Cassidy, who had supposedly survived a shootout with the Bolivian military and returned to the United States. According to De Groote, Ashworth had commissioned an analysis to compare the handwriting of known Cassidy letters with that of the supposed autobiography and other Phillips documents, which was “inconclusive.” Ashworth, however, told me that two experts had viewed the papers and both had concluded that the handwriting was that of two different people.

Read the article here:

http://www.deseretnews.com/article/700147000/Lost-Butch-Cassidy-manuscript-found.html

De Groote’s June 25 Deseret News article received little attention at the time, but it was noticed by outlaw history researchers who had been following the Phillips story for many years. In fact, not much in the article was revelatory, except that an earlier version of a long-discredited memoir had surfaced. On the newspaper’s reader-comment page, De Groote said he “was not an expert on Cassidy” and that he had “only had an hour or so to put the article together.” In a June 25 email to me, he said he was unaware of the inconsistencies in the Phillips narrative, the chief one being that Phillips was living in the United States while Cassidy was living in Bolivia, a fact that Pointer had long known. Phillips had said he escaped from the shootout in Bolivia, had plastic surgery in Paris, and gotten married in Michigan, but the shootout took place after his marriage in Michigan. Phillips also wrote of holding up trains that had not yet been built when Cassidy was in Bolivia, and he located the outlaw’s ranch in the wrong part of Patagonia. The “Bandit Invincible” clearly showed that its author was unfamiliar with the outlaw’s activities in South America.

These inconsistencies had been brought to Pointer’s attention in the late 1980s. He responded that there might have been three Butch Cassidys: the real one, who died in Bolivia; Phillips; and a supposed Cassidy relative, who later turned out to be two of the outlaw’s distant cousins who enjoyed spreading stories about him. Later, Pointer returned to his singular theory, that Phillips was Cassidy.

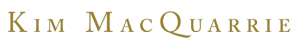

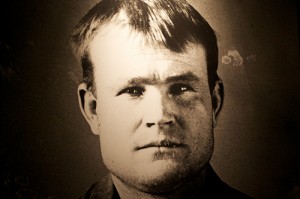

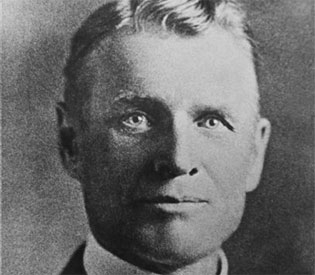

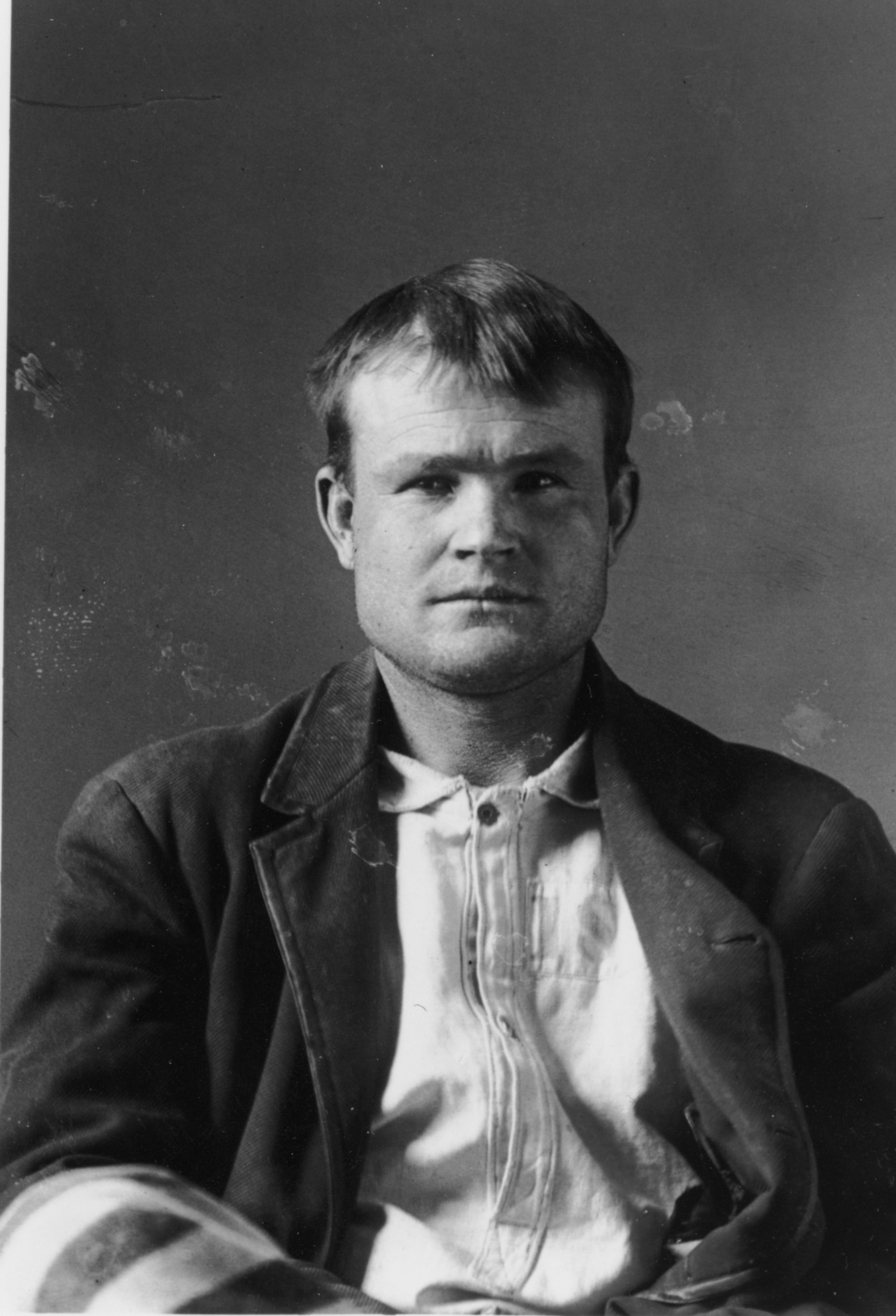

Butch Cassidy (left) and William T Phillips (right)

Cassidy, whose real name was Robert LeRoy Parker, was born in the 1860s in Utah, and Phillips was born in the 1860s or 1870s in Michigan. Cassidy and his companion the Sundance Kid, Harry Alonzo Longabaugh, likely died in 1908 in Bolivia, though that scenario remains a subject of debate. Phillips died near Spokane, Washington, in 1937. In the 1930s, while Phillips was still alive, the WPA Wyoming Writers Project had collected anecdotes from local residents about his having visited the area earlier in the decade representing himself as Cassidy. Some people who met Phillips, even some who had known Cassidy, said he indeed was the outlaw. As a result, Phillips’s death was reported in Wyoming newspapers as that of Cassidy: “‘Butch Cassidy, Old Time Outlaw, Died a Natural Death,” said the Riverton Review Chronicle, for instance.

The two leading mid-twentieth century Cassidy biographers, Charles Kelly and James Horan, were unconvinced. They dismissed the Phillips story, saying that the bandit had died in Bolivia.

The 1970s, fueled by the popularity of the 1969 movie, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, saw a renewed interest in both outlaws, especially their fates, and a cadre of new writers entered the scene, several of whom wrote books alleging the bandits had not been killed in Bolivia but had returned to the United States safe and sound. In his 1977 book, Pointer asserted Cassidy returned and became Phillips; in Butch Cassidy, My Brother (1975), Cassidy’s sister Lula Parker Betenson said he returned, occasionally used the name “Phillips,” died in the same region and year as Phillips, but wasn’t Phillips (a few years ago, her co-author, Dora Flack, told me that although Betenson had never disclosed who her brother became after his return, from everything she did say, Flack assumed he was William T. Phillips); in The Rise and Fall of the Sundance Kid (1983), Ed Kirby offered that the tall, handsome Sundance Kid was reincarnated as the gnomish, five-foot-three Hiram BeBee. He attributed the stark disparity in height and appearance to possible diseases, such as “spinal osteoporosis.” None of the writers did any research in South America, where the bandits had lived for eight years, 1901 to 1908.

Other writers later became intrigued by the mystery of the outlaws’ fate, including Richard Patterson, Donna Ernst, and my wife Anne Meadows and me. Meadows’s book, Digging Up Butch and Sundance (1994), is an account of our travels and research, our attempts to puzzle out the mystery.

The revelation of the supposed Cassidy manuscript came to the attention of Mead Gruver, a reporter at the Wyoming bureau of the Associated Press. During July, he interviewed Ashworth, Pointer, and myself, among others. His article, “Old Text, New Wrinkles: Did Butch Cassidy Survive,” appeared on the morning of August 15 and quickly went global, landing on more than 400 news sites and blogs around the world, including CBS, Washington Post, TIME, SLATE, and Deseret News.

“Utah book collector Brent Ashworth and Montana author Larry Pointer,” Gruver wrote, “say the text [of the manuscript] contains the best evidence yet – with details only Cassidy could have known – that ‘Bandit Invincible’ was not biography but autobiography, and that Phillips himself was the legendary outlaw.” Gruver, however, made it clear that this discovery was not without controversy. He quoted me describing the Phillips-as-Cassidy tale and the autobiography as “‘total horse pucky.’”

Link here:

http://www.deseretnews.com/article/700170910/Old-text-new-wrinkles-Did-Butch-Cassidy-survive.html

What Gruver did not know was that at about the same time he had interviewed Pointer, mid-July, Pointer had received information from Jack Stroud, a Wyoming man with an interest in Cassidy, suggesting that Phillips was not the famous outlaw, but was actually William T. Wilcox, who had been in the Wyoming penitentiary with Cassidy. Stroud told me in an email this week that Pointer did additional research and by August 1 was positive, as was Stroud, that Phillips could not be Cassidy. According to Ashworth, Pointer asked him to arrange an interview with De Groote, whom Ashworth had been friendly with in the past, so that he could unveil his new revelations. De Groote recalled in an email to me that he had what he called his “exclusive interview” with Pointer on August 11.

Pointer, however, was already spreading the word. “Over the next few days there will be an article in the Deseret News,” he wrote in an August 9 email to several friends and fellow researchers. “I have found information that changes, rather updates, my understanding of just who William T. Phillips: He was not Robert LeRoy Parker.” Pointer did not email the AP reporter.

Thus, by the weekend of August 13, there were two contradictory stories sourced on interviews with Pointer heading for publication, one at the Associated Press based on what was now, unbeknownst to the reporter, false information, and a second at the Deseret News, based on new information.

De Groote’s article, “Butch Cassidy Imposter Exposed,” was posted on the Deseret News website late Tuesday evening, August 16, less that 48 hours after the AP version went online.

Link here,

http://www.deseretnews.com/article/700171369/Butch-Cassidy-imposter-exposed.html

De Groote gave the impression, though in a not easily understandable narrative, that Pointer had somehow singlehandedly determined overnight that Phillips was not Cassidy. He quoted Pointer as saying the manuscript was written by Phillips, and Ashworth as saying it was written by Wilcox, without making it clear whether they were talking about one man or two. If De Groote had interviewed anyone with contrasting views about the matter, they are not mentioned in the article. I had emailed him in June, indicating that the Phillips story had serious holes. “I wish I had time to speak to you earlier,” he replied.

In any event, the August 16 Deseret News account comes across as an opaque tale of two men, possibly cousins (their mothers may have been sisters), trading identities or an opaque tale of one man with two identities. Take your pick. A Rocky Mountain rendition of The Importance of Being Earnest, absent Oscar Wilde.

The only apparent link to Cassidy was that Wilcox – or was it Phillips? – was in prison with the outlaw in the 1890s. That would pretty much eliminate the possibility that Cassidy was Wilcox. Nonetheless, Pointer was somehow “optimistic,” De Groote wrote, “that the manuscript” will lead to Cassidy. Where Cassidy might be hiding was not clear.

Cholila, Argentina , the location of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid’s Ranch

There was one final twist. After the AP story appeared, Pointer vanished, according to Ashworth, leaving him to handle the inevitable press queries. Wanting to avoid scooping De Groote’s story, which had not yet appeared, Ashworth in interviews with NPR and Radio New Zealand ducked the question of who wrote the Phillips manuscript. “‘It could very well be an autobiography. It’s either written by Butch or someone very closely associated with him,’” Ashworth told RNZ.

Links here,

“Manuscript Casts Doubt on Butch Cassidy’s End”

http://www.npr.org/2011/08/17/139696555/manuscript-casts-doubt-on-butch-cassidys-ending

“Just Who was Butch Cassidy?”

http://www.radionz.co.nz/search/results?mode=results&q=butch+cassidy

Pointer reappeared several days later, telling Ashworth he had been away celebrating his wife’s birthday. I called him yesterday to get his side of the story; he uttered an expletive and hung up. I called back; he didn’t answer.

More than 400 versions of the August 15 AP story are still congregated at news.Google.com, while the August 16 Deseret News story is in an Internet version of solitary confinement. A friend asked me why that was. I told him, “Explorers Discover Pink Unicorn in Borneo?,” is news. “Explorers Don’t Discover Pink Unicorn in Borneo,” is not news.

**

Author Dan Buck is a member of the advisory board of the Wild West History Association and a contributing editor of True West. The views expressed here are his own.